|

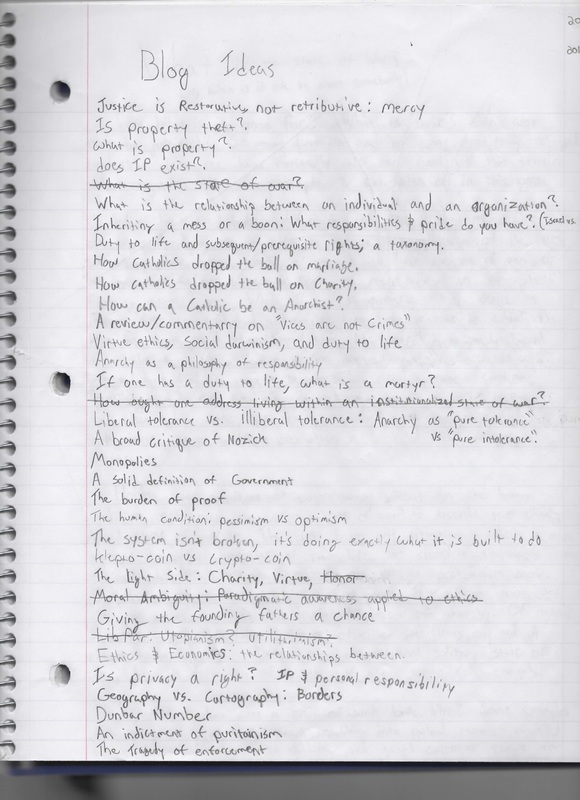

Still working on getting the nest post properly recorded, but in the mean time I have something amusing I made and wanted to share:

0 Comments

This is a scan of my notebook (obviously). This page has a list of things that I've got to write about at some point. Most of these items are partially researched and outlined and in various degrees of completion. Due to the holistic nature of philosophy, it is difficult to choose the path to follow: "I will write about X, which leads to Y, which leads to Z." Because there are many things that are prerequisite for other things: "After Y I will write about Z, but C is a prerequisite for Z, too... I guess I'll put that before Y." As I write and research each specific post, I take the things that apply to other posts and fill them in. Once something has enough material to write a post about, I clean it up, finalize the outline, record the audio, write the transcript and post it. This specific page is the first one I have filled in my notebook, so it's a little less organized and specific than the other ones I have. Some of these have more-or-less run fallow for the time being, while others are just about ready to be recorded and posted.

Suggestions for posts, comments regarding ideas on this list, comments in general are greatly appreciated. Yes, I have a real post that is just about ready to be published, I just need some quiet time in my apartment to do some more audio work, which is hard to come by with three little girls. It will be up ASAP. "Kill him!"

Several weeks ago, I made a post about the opposite of honor. It is long overdue that I should address the root of all social virtues: honor. One will notice that I write more about the handful of things that one should not do as opposed to what one ought to do. Today, I intend to shrink that ratio a little bit. What is honor? Isn't it some ancient concept that society has advanced beyond? Isn't honor something like following the orders of your superior? That's not very anarchist... Wouldn't an anarchist denounce honor societies out-of-hand?

A more important issue to address than these questions lurks behind the ivory paywalls of academic literature and the veil of history. Modern conceptions of honor are, fundamentally, the opposite of the true nature of honor. Popular culture and medieval theological writings conceive of honor as dutiful obedience to one's leaders and adhering to social norms. This conception of honor is comically shallow and presents a great deal of self-contradiction, as is explored by numerous sci-fi and fantasy works. I don't have the space and time right now to address this unintended straw man and all of it's problems which have been created by history. Instead, I will have to simply define and describe true honor. So, forget anything that you have seen about honor that was produced since Marcus Aurelius, and come with me to the ancient world. -cue time-travel harp and ancient-sounding music- Ancient Greece, a region populated with several dozen city-states: some of them more free than others, some of them ruled by kings, some ruled by mobs of slave owners, some of them were pseudo-hierarchical warrior cultures. This region and time is credited with the birth of philosophy as we know it as well as serving as the foundation of western culture. It was also a time and a place, like all places and times with states, a region constantly faced with the prospect of war. In order to flourish in such a region, one would have to either submit to being owned by a powerful man or engender virtues in oneself such so as to be self-sufficient. There are different types of virtue, and flourishing in its fullness requires all of the virtues, but today is devoted to one specific virtue. Honor is a social virtue. It is an internal, personal disposition to certain behaviors that concern themselves with one's relationships with others. Honor is a virtue that can only be developed in community, but what is it? The original words for honor, which later became the Greek kleos and the Latin dignitas, originally meant something akin to “trophy”. It was a physical object which represented an accomplishment that would be given from the community to the individual responsible for the accomplishment. Most often, honors were the spoils of war granted to the soldier who demonstrated how one ought to conduct themselves in battle. Other times, though, honors would be granted to those who demonstrated how one ought to innovate, parent, lead, teach, or even farm. These honors would be given publicly and were expected to be displayed publicly. Over time, honors as physical trophies became overshadowed by honor as a social reputation. An honorable person was one who demonstrated a paradigm behavior that others could acknowledge. In this way, honor was essentially setting the example. During this time, there existed an interesting linguistic situation. The word for honor represented a single, integral concept that modern languages have teased apart and made two diametrically opposed terms: honor and shame. Honor, like many ancient concepts, was a very complex and rich tradition which defies surface exploration. It was a trophy, a reputation, and a feeling all bundled into one. These were nearly indistinguishable from each other and the same term applied to each of the three independently at times. When one received or established their honor, they would have a particular set of feelings associated with that accomplishment. When put on a pedestal, one ought to feel self-satisfied and proud, even. One ought to be humbled by others' recognition of one's accomplishments, and feel a certain degree of self-consciousness or nervousness. I'm not saying this as an introvert who doesn't like attention, but because of the nature of honor; at the heart of honor is an expectation of integrity and consistency. Having demonstrated one's character such so as to be granted honor means that the village children will be pointed to oneself as the role-model: “You see, little Apollonius, if you want to be magnanimous, try to be like Alexander, son of Phillip.” Alexander ought to feel the eyes of his neighbors and inferiors on him at all times, scrutinizing his actions. Alexander has no obligation to his inferiors. He has no moral obligation to uphold his honor, especially since it would have to be given to him from someone else, freely and without solicitation lest it would be meaningless (much like the medals on a President's uniform). Meaningful honor cannot be granted to one's self. Of course, if Alexander drops the ball, finding work may become difficult. There is a certain circumstance of expectation for one with honor which must be taken into account if one wishes to flourish. These feelings and circumstances should look familiar to those acquainted with the modern religious concept of shame. Initially, as western cultures developed terms for shame, it was essentially synonymous with humility. Not the flimsy Thomist “just roll over and take it” version, but the ancient stoic “don't exaggerate your accomplishments, just be aware that you are being watched and let your actions speak for themselves” version. Shame originally meant “the feeling you should get concerning your honor,” which used to be the meaning for the word “honor” when used in the context of feelings. Incidentally, some cultures would honor undesirable behavior, as well. One would be honored for their cowardice, dishonesty, or promiscuity. In which case, the shame felt would be more akin to the popular modern conception of the term. This specifically, is simply a fun bit of trivia as far as the issue at hand is concerned, but it may come up in later posts. What is important to the issue at hand? So far, we've only tried to clear up some small degree of confusion regarding a term that has been repeatedly co-opted throughout history. We haven't really defined or described it. So, what is honor and what does it look like? As I already said, honor is a social virtue: a virtue pertaining to the manner in which one relates to others. It is essentially setting the example. What kind of example? An example of virtue. Ancient virtue. Virtue, as a Latin word, really means “manliness'. Manliness meaning “the paradigm example of what a human ought to look like, in appearance and behavior.” I will make a post later about virtue specifically, but for now I will focus on the attributes of honor. Honor is a demonstration of virtues such as integrity, justice, courage, and self-actualization. A man of honor, ultimately, is a man who is free and willing to do the most righteous thing without the aid or encouragement of others. Instead of saying “someone ought to do X” or “There ought to be a law”, a man of honor simply does X and demonstrates how it ought to be done without seeking payment or recognition. Clearly, honor is a virtue largely contingent upon other virtues. One cannot, for example, step-in when someone is committing a crime against someone unable or unwilling to defend themselves unless one first possess virtues like courage, magnanimity, and the martial virtues. One cannot engage in intellectual pursuits and eloquently and passionately introduce others to esoteric knowledge unless one first possesses the virtues of diligence, discipline, and reason. Unlike crime, honor is more fluid and less axiomatic in its specifics. However, it's definition is quite helpful in identifying honor when one witnesses it. Honor is a character trait whereby one is prone to consistently demonstrating exceptional virtue in their interactions with others. Remember, anarchy is a philosophy of responsibility. In the absence of the perpetual threat of murder for disobedience to arbitrary moral claims, alternative cultures of cooperation must endure. Honor, shame, and social relationships have always been crucial to the functioning of free societies. TL;DR: Instead of confusing honor with a pseudo-Christian bastardization of servitude and approval from one's masters, one ought to read ancient Greek ad Roman stoics and scholarship concerning them. Honor is centered on the social virtue of living well and setting the example as to how one ought to flourish. Who is John Galt? Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the marketplace, and cried incessantly: "I seek God! I seek God!" As many of those who did not believe in God were standing around just then, the madman provoked much laughter. Has God got lost? asked one. Did he lose his way like a child? asked another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? Emigrated? Thus did they shout and jeer.

In Catholic culture, it is common to describe someone's personality, temperament, and spiritual charisms by way of a particular analogy. There are “Good Friday people” and “Easter Sunday people”. I believe there is a protestant equivalent of “Old Testament people” and “New Testament people”. Good Friday people tend to be more prone to despair, legalism, talk of duty and fire and brimstone; Catholic guilt runs deep in Good Friday circles. Easter Sunday people, alternatively, tend to be more prone to wearing rose-tinted glasses, overemphasis on mercy and forgiveness and belief in happy-surfer Jesus; liberalism tends to creep into Easter Sunday circles. Now, these are, of course, caricatures intended to convey a point to people who are less-involved in Catholic culture, but the claims are still valid. I used to think I was a Good Friday person, with my tendencies towards the Metal ethos and pathos. As time went on, though, I realized that my particular brand of duty, guilt, and forgiveness do not match the generally-accepted sense of a Good Friday person.

I live in the world of Holy Saturday. I live in a world in which we have killed God and have to live with his blood on our hands. What does such a world look like? It is a wold where, yesterday, we knew where we were going, what we were doing, and we had a direct line to the divine, He was sitting right next to us at the dinner table. Today, however, he is gone. He is somewhere we cannot see and we can't even prove to ourselves that He didn't just vanish altogether. Today, we don't know anything more than the fact that we are lost, adrift in a world devoid of the meaning it once held. We hope that tomorrow, He will come back and fulfill all of the promises that were made... but we can't be certain that it will happen. We thought we had it all figured out, and then (even though we were explicitly warned) we were surprised by the execution of our Lord and our subsequent despair associated with it. If this world looks bleak and unrealistic, that's fine. It certainly is bleak, but not unrealistic. We face certain epistemic crises that remain unresolved. The problem of induction, which has no solution, tells us that we cannot truly prove anything meaningful to our lives through experience or reason. The eschatological questions: “What happens when I die?” and “What happens if the world ends?” cannot be answered with any degree of certainty and all we have to go on are some well-reasoned guesses and books written thousands of years ago by people who claimed to have a direct line to the Truth. In other words, even though God himself may, in fact, be the cookie elevated in sacrifice over the altar tonight, I have absolutely no way to tell. All the empirical tools I have at my disposal tell me it is just a cookie, and the best logic can provide me is a well-reasoned guess that it may be more than it would seem. I have to accept that guess on faith, though, the same faith that tells me that the sun will rise tomorrow and that others experience consciousness in a manner comparable to my own. Even more difficult to rationally explore and prove would be the idea of life after death and redemption versus damnation. However, as Paschal thoroughly explored in his corpus, there is quite a lot at stake here, and guesswork is ultimately all we have. I find myself compelled to carry out my affairs in a manner consistent with this tension between nihilistic despair and extra-rational faith. I must act in a manner consistent with my own human flourishing in this life, but always with an awareness of the possibility of an after-life as well. Ultimately, it is the only rationally self-interested way to approach the horns of this dilemma which surpasses our limited human perception and reason. This isn't to say that I don't try to engender a healthy and fulfilling relationship with God, only that it is incredibly difficult to do so when His only avatars are other human beings as equally repulsive as myself and a silent piece of bread. The tension of Holy Saturday is the tension of being a rational creature both unwilling to despair and unwilling to forego the ratio which allows this tension in the first place. It is the tension of the philosopher, of seeking Truth, despite the impossibility of fully acquiring such a thing. It is the tension of the pilgrim in a foreign world. It is the tension of a moral actor amidst the amoral. It is the tension of a sinner, a criminal, a vicious creature striving for something greater, striving for perfection, a will to power, an upsurgence of life, and a desire to flourish in a world that is finely-tuned to allow for one's existence but only barely so. It is the tension of being truly Catholic. “I am reckoned among those who go down to the Pit; I am a man who has no strength, like one forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom thou dost remember no more, for they are cut off from thy hand. Thou hast put me in the depths of the Pit, in the regions dark and deep.” ~ Psalm 88 |

Children learn many principles of natural law at a very early age. For example: they learn that when one child has picked up an apple or a flower, it is his, and that his associates must not take it from him against his will.

Lysander Spooner The MadPhilosopher Podcast Feed is right here:

http://feeds.soundcloud.com/users/soundcloud:users:120358620/sounds.rss Archives

October 2015

Categories

All

Donations are also graciously accepted. This is a surprising tax on my time and resources, but it's a labor of love. Just because it's a labor of love doesn't mean it has to go unrewarded.

Public Bitcoin Tip Address: 171eB18Yg39JpkLrrL8Wji5kj1ATGoyPay |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed