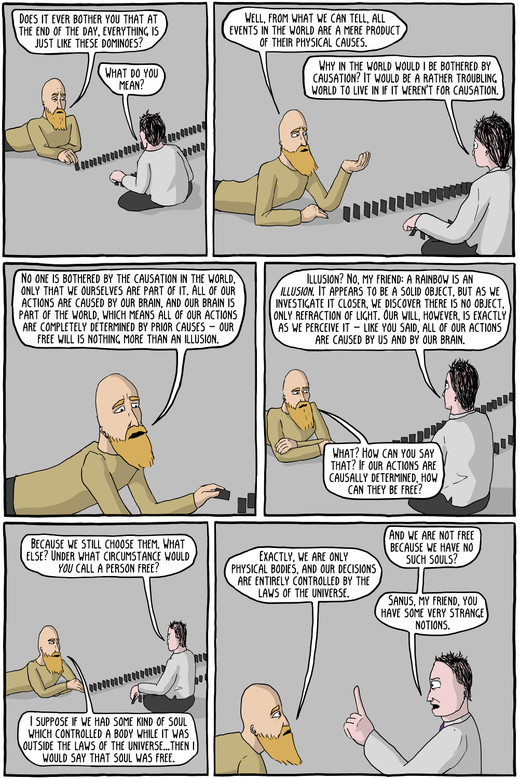

You see, I'm a deontologist of sorts. It's no mistake that my last post was about ethics. Deontology, at least my particular brand of it, is an ethical framework centered on moral absolutes and individual action. In other words, I believe that, regardless of circumstance or outcome, murder, coercion, and theft are categorically immoral. I believe that the ends never justify the means and that ethical reasoning applies exclusively to the decision at hand and not the past or the future. Considerations of goals, intentions, consequences, etc. only enter the picture after the moral absolutes sort out the morally justified and the unjust actions available. Alternatively, after one determines the most desirable course of action based on such considerations, one must verify that it does not violate moral absolutes. This is all a direct result of my broader philosophy, but that discussion is best left to another place and time.

If Deontology Man were a superhero (he'd be Rorschach), he would need an arch-nemesis. This arch-nemesis would be (Ozymandias) The Utilitarian and his sidekick/son, Consequentialist. Utilitarianism is a sterile, mathematical approach to life and ethics. Its goal is to maximize quantifiable pleasure for the maximum number of people. Imagine giving Spock or the T-800 the keys to the kingdom and the directive of maximizing everyone's pleasure. Best case scenario, you'll find yourself in a Peter Singer (advocate of murdering retarded kids and granting whales constitutional rights) book; worst case, scenario, you get “The Matrix”, but with more robot sex slaves and limitless cocaine.

What does deontology and utilitarianism have to do with LibPar and utopia? You'll see, but we mustn't forget Consequentialist. Consequentialism is a form of utilitarianism which uses the results of an action to retroactively determine whether or not it was a morally good or bad action. In the example of the miraculous “abolish government” button: if my guess were correct, it would be good to push the button and if we wound up with Mad Max, it would have been bad. A lot of people are sympathetic to this line of reasoning; a law can be called a good law or a bad law based on whether we think it improved or detracted from people's quality of life... but, by that logic, if someone were to have brutally murdered Maria Schicklgruber in the 1700s, it would have been a morally good act, by way of preventing Hitler from ever existing: ignoring, of course, the impossibility of knowing about the possibility of Hitler in a world where his grandmother was murdered. As a matter of fact, I will milk Godwin's law even further: modern medicine and space travel, invented by Nazis, have saved and improved more lives than those lost or ruined in the Holocaust, so Hitler was a good guy.

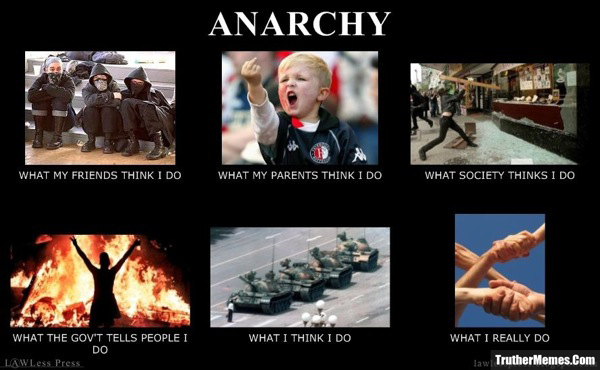

Now we have arrived at anarchy and LibPar. I tend to avoid discussions about Liberty Paradise, except behind closed doors with close friends. People like to (incorrectly) brand anarchism as a utopian philosophy and ridicule it as such. Way back in “Towards a Definition of Anarchy”, I explained that anarchism is not a positive, goal-oriented philosophy but instead is a proscriptive moral claim against criminal institutions. Due to the nature of anarchism and my deontological leanings, discussions as to “the ends in mind” when discussing anarchism vs. statism is inappropriate; such discussions distract from the importance of the issue at hand, namely, “How ought I conduct my affairs in this moment?”

That said, I can engage in a discussion of what I expect LibPar to look like, so long as we keep in mind this important principle: the rest of this post is not a discussion of the necessary result of people behaving in accordance with the principles of anarchy, it is an assessment of a likely possibility, based on my understanding of the human condition and experience. LibPar is a fairy tale that, like the utopian visions of democracy, have no influence on the daily actions of anarchists.

LibPar:

In an ideal state of affairs, I would have the “abolish government” button handed to me from on high and I would make every institution proscribed against in “Towards a Definition of Anarchy” vanish overnight. Yes, the world may be rendered chaotic and in a state of violent upheaval. Some, less domesticated, places would likely continue operations as if nothing had changed, while others may burn to the ground... Of course, that's what’s happening right now, just on a longer timetable. In a less ideal, but more realistic, state of affairs, the message of freedom and responsibility may reach a sufficient number of people and technology may progress to a point so as to enable the widespread adoption of these beliefs in action. Regardless of the specific events which would lead to the formation of LibPar, what would it look like?

Markets:

Firstly, unlike utopian outlooks, I have no specific design for how the entire world ought to work. I expect, in the open market of ideas and philosophies, that a plethora of societies will form worldwide, each with their own distinct features; some will be better suited for perpetuity while others will not. Such is the way of things; without governments to artificially sustain bad ideas, some societies will collapse under their own weight, while others will flourish if genuinely allowed to compete.

This will likely result in different economic models, such as pure capitalism and pure socialism (think first century Catholics, not USSR or USA), being granted opportunities to succeed without the interference of government guns. So will various alternative markets: gift economies, barter and service, token economies, “smart” economies (think blockchains), honor markets... the theoretical options are limitless. Without global market manipulations and capture, we would actually get a chance to see if any of them work in practice. I have a couple that I'm rooting for, but that's unimportant.

Dunbar Number:

The human condition is such that we have the capacity for a limited number of meaningful human relationships that one person can maintain at any given time. Anarchist societies will have to reflect this reality in some way. I expect the most likely way the Dunbar Number will be expressed is that such societies will consist of a few hundred or a maximum of one or two thousand. Such a small population also helps prevent the rise of criminal institutions and most considerations delegated to the state in slave societies will simply not be present in a small enough population. Additionally, genuine human interaction becomes essentially unavoidable, the inverse case of urban environments. The essential quality of the Dunbar Number is that, in a community of appropriate size and density so as to promote human flourishing, you would know everyone by name.

Recently, a friend asked me how a small community marketplace could solve moral issues that people generally turn to law to rectify. The example in question was that of strip clubs, which we both find morally objectionable, but not criminal. The Dunbar number, and small community is the way I think the issue naturally gets solved. Stripper Stacy becomes a lot less fun when you know her parents, she lives down the street, and she knows you and the three other dudes that visit the strip club outside of the club. Also, statistically speaking, Stacy is likely to be the only one in the community that would be willing to be a stripper, which would make it more of a small-business-out-of-your-basement kind of operation, which resembles a strip club solely by way of the vicious nature of the specific service. It does not necessarily mean that the service goes away, but it certainly mitigates the impact on the community as well as making a coercive and violent law regarding it superfluous.

Intentionality:

With a population so small, such a community can be centered around a common goal or ideal. Closely tied to the market of markets, there is an infinite number of possible intentional communities: Catholic parishes, hippie communes, AnCap fiefdoms and marketplaces, farming co-ops, tech outfits, brony conventions, and Amish fellowships all come to mind as possibilities. Some may last longer than others, but as long as people are wiling to experiment there will always be a diversity of intentional communities. These societies already exist around the globe, they land all along the anarchist/statist scale, but as a proof-of-concept, they have demonstrated that such a community can flourish over an extended period of time. Ideally, I would like to live in a familial tribe centered around a certain philosophical bent, pursuit of virtue, and self-sufficiency, but that is neither here nor there.

Mobility and Intercommunication:

Simply put, communities of such small populations and of diverse ideas could only be sustainable themselves if mobility from one community to another and the ability to form new ones is a possibility. Additionally, if a community consists of only a few hundred people, the gene pool may get a little shallow without exchange of populations between different communities. Of course, such migration is inevitable if people trade with, communicate with, and travel to other communities. This will rely on technologies similar to the internet, if not the internet itself and technologies like trucks and boats and such... but we've had such technologies for a while now. It's not too much a concern. Really, freedom needs to be open-source, which would allow for exchanging good ideas between communities and the opportunity to copy what works and improve on what is available.

Security:

There are a multitude of ways that an individual can render themselves "secure". One such manner is with the proper tools and training (AKA guns and the ability to shoot them), another would be a nomadic lifestyle, another would be remoteness (if no one can be bothered to seek you out, they can't bother you), another would be to position your hippie commune such that it is surrounded by radically isolationist militia-type communities... the list of possibilities is longer than I can come up with on my own. What is important is the ability for individuals within an intentional community to defend themselves from others in their community and those around them.

Sustainability:

I don't mean the liberal socialist environmental bullshit, but instead focusing on options which are either cost-neutral or renewable. An example would be making sure one does not deplete the surrounding ecosystem or raw materials (growing hemp permaculture rather than resorting to deforestation and mass agriculture for paper, textiles, construction materials, etc.) or carefully managed hatcheries separate from the native population of fish, or nuclear/passive power generation as opposed to fossil fuels. Not for any pie-in-the-sky theories about preventing global warming or whatever, but because reliance on sustainable resources and infrastructures eliminates the spectre of “the tragedy of the commons” as well as eliminating the need for state institutions built for subsidizing irresponsible industrial practices.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed